History Has Not Yet Been Told

Late in the year 1990 I met Tim and Sharon Hansen, Fulbright scholars who were touring India. Although they were a good 30 years older than me, we hit off well. Tim gave me a manuscript of a book he was co-authoring, called “Parallels: The Soldiers’ Knowledge And The Social Definition Of War.”

The manuscript consisted largely of interviews with Vietnam war veterans, reliving their war experience. In the introduction the authors mention:

This material was made available to us through a unique and interesting process. In the spring of 1989, the interdisciplinary Vietnam Studies Program at the University of Puget Sound began a series of exchanges with the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Program at the American Lake Veterans’ Hospital near Tacoma, Washington. Our students believe that the war in Vietnam, and its aftermath have been slighted in their education, and the veterans find it therapeutic to communicate with an age group they have long distrusted. Participation is purely voluntary on both sides. Veterans come to the campus for “Vets’ Nights” and our students go to the hospital to record their oral histories.

What motivated the authors to choose this particular form of documenting history? They explain in their introduction:

We believe that the first-hand memories of soldiers provide a reliable, critical perspective on contemporary wars. Even a cursory reading of these narratives reveals devastating criticisms of various “official” views of warfare. Formal analyses by retired officers, historians, political leaders, and academicians have been privileged in public debate. As Michel Foucault and his followers have shown, the public have been taught to think that abstract, cognitive analyses of war are more objective, more in-depth, and more reliable than the soldier’s knowledge. Veterans are thereby marginalized, ignored or overlooked and unable to make their voices heard. Our intention is to empower the soldier’s knowledge by making it available to the public in published, and therefore more authoritative form. These recollections – history from the bottom up – present damaging criticisms of military definitions of war.

This is what lies at the heart of oral history. History from the bottom up.

According to the Oral History Association, the term oral history refers to “a method of recording and preserving oral testimony” which results in a verbal document that is “made available in different forms to other users, researchers, and the public.”

Oral history can be powerful, because it relives trauma, pain, anguish. It can expose personal histories, family histories. It can reveal life in small nondescript villages and shanties that academics have ignored. It can throw you right into the blood and gore, the chaos and bedlam of war.

Here is one such account from Hansen’s manuscript:

I was flying through the air, hit the ground, slid into the ditch. The jeep came flying in on top of me… There wasn’t much left of Junkie… His whole upper torso was gone. I lost it… I just lost it. I was trapped under the jeep, all this shit was going on, and I couldn’t get out. I was bleeding through the mouth. I was trapped under the jeep for a good 20 minutes while explosions were going on around me. I couldn’t holler to anyone… And I really freaked out. They almost missed me. They got me out and I was flown back in to Duc Pho where they had an aid station. I came out of that with just cracked ribs and some bad lungs.

The only other significant thing during this time was the first time I was in close combat. We got overrun one night. They got through to us. They came through the wire near the bunker I was in. Bunkers are L-shaped so explosions can’t get straight into them. When they penetrated the wire one man in the bunker was to go out to the back door. I went running around the corner and ran straight into a sapper. We both hit the ground… And I remember just freaking out. I had to back up to shoot him. It was weird… Everything in his head was gone. His face was there, but the eye sockets were empty. I emptied his whole head out, and it all happened in an instant.

The authors are all too aware of the problems that a historian faces when using oral recollections. Especially in the theatre of war. They quote David Hackworth, author of “About Face”:

The […] problem is that they have their genesis in the fog of war. In battle, your perception is often only as wide as your battle sights. Five participants in the same action, fighting side-by-side, will often tell entirely different stories of what happened, even within hours of the fight. The story each man tells might be virtually unrecognizable to the others. But that does not make it any less true.

Nevertheless, Hansen and the other authors say: The soldiers’ knowledge in these narratives has a number of claims to its authority.

In June 1944, United States Army historian Forrest C. Pogue picked up a wire recorder on a hospital ship off Omaha Beach and began interviewing soldiers wounded in D-Day battles. His interviews, done under the direction of chief army historian S. L. A. Marshall, helped lay the groundwork for the development of oral history as a research technique.

The genre grew in volume and stature after the war. It was largely fueled by a sizeable body of literature on World War II, especially the Holocaust. These have employed the category of “memory” to explore lived experiences of survivors of traumatic events that conventional historical methods cannot capture.

But is memory accurate? Such works on traumatic experiences have often been criticized. The authenticity of the telling questioned.

The authors of “Survivors: An Oral History of the Armenian Genocide”, reply:

We actually have some sympathy with the charge that survivors remember “tales of horror … in such detail as to astonish the imagination.” Indeed, we ourselves have often been amazed by the specificity of survivor recall. However, rather than discrediting the testimony because of its detailed nature, we have been drawn to ask a different question: namely, what accounts for the remarkable quality of survivor memory?

We believe the answer to this question lies in the exceptional nature of the events described: fathers being shot or tortured, mothers and siblings being sexually abused, children being abducted, and a litany of other horrors. Such memories are not easily forgotten. Indeed, they seem to be burned irrevocably into the consciousness of survivors. They dream about them at night. They have an incessant, even obsessive, need to talk about these events.

Alessandro Portelli, author of “The Order Has Been Carried Out- History, Memory, And Meaning Of A Nazi Massacre In Rome”, writes:

One of the differences between oral and written sources is that the latter are documents while the former are always acts. Oral sources are not to be thought of in terms of nouns and objects but in terms of verbs and processes; not the memory and the tale but the remembering and the telling. Oral sources are never anonymous or impersonal, as written documents may often be. The tale and the memory may include materials shared with others, but the rememberer and the teller are always individual persons who take on the task of remembering and the responsibility of telling. Settimia Spizzichino, the only woman survivor among the Jews deported on October 16, 1944, said: “I made a promise when I was in the camp, I made a solemn promise to my companions, who were being picked out [to be killed] or dying from disease and abuse. I rebelled, I didn’t know whether to curse God or pray to Him, and repeated over and over, Lord save me, save me, because I must go back and tell.”

From the front piece of Tears Before The Rain:

I don’t want my memories to be lost, like tears in the rain. So I will tell you my story. Then you can tell it to others. Maybe if enough people know what happened to Vietnam, then my memories will never be lost. Maybe then they will be like tears before the rain. So listen. This is very important. This is what I remember. This is what happened to me. These are my tears before the rain.

- Duong Gang Son

Orality, and memory, are also forms of rebellion. They go against the grain of conventional academic/professional historianship. Historian Prachi Deshpande, in her book “Creative Pasts”, writes:

In recent years the category of Memory has emerged as a prominent framework to examine cultural practices through which groups represent the past. Much of the scholarship that has led to the Memory boom has followed two broad tracks. One major strand contrasts memory and history, the latter seen as replacing the former after the Enlightenment in the West as a more critical, rational, and scientific appreciation of the past. This approach suggests that history came to view the past as more distant and objectified, and gradually eroded spontaneous connection with it and its presence in everyday life. Scholarship on technology and culture has reinforced this view, tracing a linear development from oral myths, legends, and texts in mnemonic verse that provided an unbroken, living connection with the past to a critical distance and exteriority introduced first by literacy, and later, more emphatically by print. Broadly then, memory and history, orality and literacy (and, very often, non-West and West) have appeared as homologous binaries placed along a linear, unfolding path from tradition to modernity. This has resulted in the renewed privileging of memory as an elusive, yet more legitimate means of getting closer to the past.

“Event, Metaphor, Memory, Chauri Chaura 1922-1992”, by historian Shahid Amin has been hailed as a path-breaking academic work.

On 4 February 1922, peasant volunteers who had enlisted in Gandhi’s newly launched people’s struggle against the British rule turned violent and burned down a police station of “Chauri Chaura”, killing 23 policemen. According to Shahid Amin, this dramatic occurrence simply had to be quickly forgotten as a stain upon the clean sheets of country and nonviolence.

And so it indeed was. Shahid went back seventy years later, and interviewed relatives of the rioters, to try and recreate the history of those events. He also referred to police records of the inquisition that followed. But testimonies in court inquiries that followed came mainly from the accused. These voices were thus muted. In his prologue he writes:

When writing histories of the unlettered – workers or peasants who produce goods and services, not documents – it is now conventional to latch onto extraordinary events in the lives of such people. Peasants do not write, they are written about. The speech of humble folk is not normally recorded for posterity - it is wrenched from them in courtrooms and inquisitorial traps. Historians have therefore learned to cope with confessions and testimonies for the evidence, for this is where peasants cry out, dissimulate or indeed narrate. Like other members of my tribe, I have in this book attempted to interrogate the interrogators. In order not to write like the judge, I have tried to find out how the judge wrote.

|

|

|

|

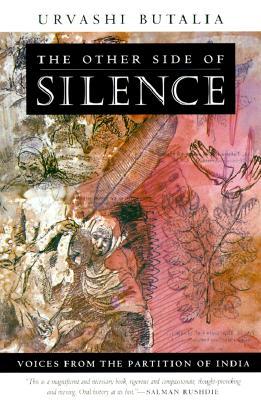

In India there has been a spate of books in the recent past which use oral history and memory to recount the trauma of partition in 1947. Take for example, Urvashi Butalia’s “The Other Side Of Silence: Voices From The Partition Of India”; Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin’s “Borders And Boundaries: Woman In India’s Partition”; Gyaendra Pandey’s “Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism, And History In India” and “The Partition Of Memory: The Afterlife Of The Division Of India” edited by Suvir Kaul.

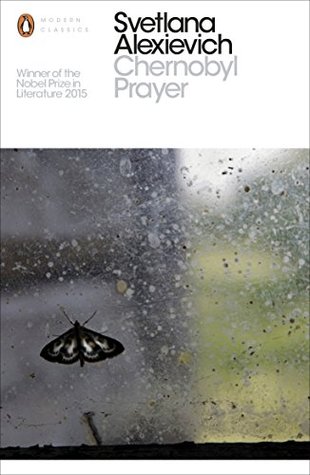

Endorsement and recognition for the format has come as a Nobel Prize. In 2015 Belarus journalist Svetlana Alexievich won the Nobel Prize for Literature. The motivation, as stated by the Committee, was “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

She writes in Russian, about Soviet/Russian experiences. Notable books have been “Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from a Forgotten War”, about the Afghan war experience, “Chernobyl Prayer / Voices from Chernobyl”, and of course, her first book “The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II”.

Here’s an excerpt:

Near Kerch…We went on a barge at night under shelling. The bow caught fire…The fire crept along the deck. Our store of ammunition exploded…a powerful explosion! So violent that the barge tilted on the right side and began to sink. The bank wasn’t far away, we knew the bank was somewhere close by, and the soldiers threw themselves into the water. There was machine-gun fire from the bank. Shouts, moans, curses…I was a good swimmer, I wanted to save at least one of them. At least one wounded man…This was in the water, not on dry land—a wounded man perishes at once. Goes to the bottom…I heard somebody next to me come up to the surface, then sink down again. Up—then down. I seized the moment and grabbed hold of him…Something cold, slimy…I decided it was a wounded man, and his clothes had been torn off by the explosion. Because I was naked myself…Just in my underwear…Pitch dark. Around me: “Ohh! Aiie!” and curses…I somehow made it to the bank with him…Just then there was the flash of a rocket, and I saw that I was holding a big wounded fish. A big fish, the size of a man. A white sturgeon…It was dying…I fell down beside it and ripped out some sort of well-rounded curse. I wept from rancor…And from the fact that everybody was suffering…

Svetlana has said: “I’m searching life for observations, nuances, details. Because my interest in life is not the event as such, not war as such, not Chernobyl as such, not suicide as such. What I am interested in is what happens to the human being, what happens to it in of our time.”

In her Nobel acceptance speech, she said: “I do not stand alone at this podium … There are voices around me, hundreds of voices. They have always been with me, since childhood. … Here are a few sad melodies from the choir that I hear …

First Voice:

“Why do you want to know all this? It’s so sad. I met my husband during the war. I was in a tank crew that made it all the way to Berlin. I remember, we were standing near the Reichstag – he wasn’t my husband yet – and he says to me: “Let’s get married. I love you.” I was so upset – we’d been living in filth, dirt, and blood the whole war, heard nothing but obscenities. I answered: “First make a woman of me: give me flowers, whisper sweet nothings. When I’m demobilized, I’ll make myself a dress.” I was so upset I wanted to hit him. He felt all of it. One of his cheeks had been badly burned, it was scarred over, and I saw tears running down the scars. “Alright, I’ll marry you,” I said. Just like that … I couldn’t believe I said it … All around us there was nothing but ashes and smashed bricks, in short – war.”

Second Voice:

“We lived near the Chernobyl nuclear plant. I was working at a bakery, making pasties. My husband was a fireman. We had just gotten married, and we held hands even when we went to the store. The day the reactor exploded, my husband was on duty at the fire station. They responded to the call in their shirtsleeves, in regular clothes – there was an explosion at the nuclear power station, but they weren’t given any special clothing. That’s just the way we lived … You know … They worked all night putting out the fire, and received doses of radiation incompatible with life. The next morning, they were flown straight to Moscow. Severe radiation sickness … you don’t live for more than a few weeks … My husband was strong, an athlete, and he was the last to die. When I got to Moscow, they told me that he was in a special isolation chamber and no one was allowed in. “But I love him,” I begged. “Soldiers are taking care of them. Where do you think you’re going?” “I love him.” They argued with me: “This isn’t the man you love anymore, he’s an object requiring decontamination. You get it?” I kept telling myself the same thing over and over: I love, I love … At night, I would climb up the fire escape to see him … Or I’d ask the night janitors … I paid them money so they’d let me in … I didn’t abandon him, I was with him until the end … A few months after his death, I gave birth to a little girl, but she lived only a few days. She … We were so excited about her, and I killed her … She saved me, she absorbed all the radiation herself. She was so little … teeny-tiny … But I loved them both. Can you really kill with love? Why are love and death so close? They always come together. Who can explain it? At the grave I go down on my knees …”

|

|

|

In oral history, the role of the journalist and the historian have fuzzy boundaries, even if their motivations are somewhat different.

In Tears Before The Rain, CBS Reporter Mike Marriott recounts:

I was the cameraman on that last flight up to Danang. Bruce Dunning and Mai Van Due and I got permission to go along with Ed Daly. When we asked him for permission to go along, he said, “Sure, the more the merrier.” When we came in for the landing in Danang, the twin runways were perfectly clear, and there was not a person near the runways or the taxiways or anything. And there seemed to be no one around the hangars. It seemed contrary to every report we had heard that Danang was about to fall. We had expected to see panic in the streets and wild mobs. We could see the city of Danang, too, and the streets were quiet. So we landed.

We started to pull off the active runway onto the taxiway when suddenly, out of every hangar—and it was a huge airbase that had served most of the U.S. Air Force during the war—there must have been 20,000 people suddenly heading toward our aircraft. They were in jeeps, on motorcycles, in tanks and personnel carriers—in about every kind of vehicle known to mankind—and they were all coming toward us. We stopped between the two runways for a moment. My camera was running. We were all going to get off before we saw all those people. Then, all of a sudden, I got a gut feeling—it was one of those feelings you get when you’re covering a war. And I said to myself: “Don’t get off this plane. Those people are panic-stricken. Anybody, no matter how small they are, if they panic, they’re stronger than you are, Mike.”

I went to the back air stair to take some pictures of what was happening. We were still moving around the airfield, and people were running up the ramp. They had come over the side of the ramp and bent it so that it was impossible to pull it up again. As I was filming, they started shooting each other. They were shooting each other in the back to get closer to the aircraft. That’s when I turned and said to Bruce, “We are in deep shit!”

We taxied all around the airport. Then Daly finally just made a decision. He said, “Let’s get the hell out of here.” At that moment we started to take off down the taxiway. We hit a vehicle as we started to lift off. Our left wheels clipped a jeep. I thought at first that maybe we were just taxiing, because I was still standing on the air stair. Then suddenly, I heard the engines wind up and I thought, “Oh, shit! And I’m still on the steps.” I did not want to fall down those steps. And there were five Vietnamese below me on the steps. As the nose of the aircraft came up, because of the force and speed of the aircraft, the Vietnamese began to fall off. One guy managed to hang on for a while, but at about 600 feet he let go and just floated off—just like a skydiver. I watched him fly away.

And here’s one last account to end this piece:

We all knew the war was coming.

The Nilmoni school field had been occupied by khaki clad men in metal barracks (Quonset tents) for some months.

One morning when I woke up and walked to the field, they were all gone. In their place were tall olive-green wearing gaunt men. Between the metal barracks were columns and columns of field guns.

We all knew the war was coming.

We knew we would win.

The headlights of all the cars had been painted black on the top half. So that bombers would not be able to spot the lights from the skies.

We were told to glue strips of paper in an X shape, onto our glass windows, so they would not shatter if the bombs fell close to us. Projit, who used to work for my grandfather, was a genius of a craftsman. He could make beautiful toys out of paper and wood. He set out to cut beautiful patterns from brown paper. These designed strips of paper he glued on onto our glass windows with meticulous care.

There was a silver painted bridge over the Noti-khal, a canal that ran through the town. They painted the bridge green to match the moss and hyacinth of the canal below.

We were ready for war.

Indira Gandhi had wanted to enter East Pakistan as early as March. Sam Manekshaw told her that India needed time to mobilize. Besides, the impending monsoon would wash out the army in East Pakistan.

As mobilization built up day after day, I saw the tanks rolling in into the valley. The Jowai road, which was a thin one-way lifeline to our far-flung corner, was rapidly widened to let the forces come in.

Endless convoys of Shaktiman trucks, Vijayanta tanks and QF 25 pounder field guns rolled into the Barak Valley. And Amphibian Vehicles.

As December approached, womenfolk of the house were told to go out only with their “ghomtas” (ghunghat) pulled down over their faces. The Baloch regiment across the river should not recognize their faces.

Sand bags were piled up high in front of the house to stop bullets. On the river bank pill boxes had been dug in. Artillery nozzles poked out of holes ominously, aiming out across the river.

This story has not been published. It’s my story. A fragment of my memory of 1971.